Tōku Pāpā

Tōku Pāpā by Ruby Solly. Wellington: VUP (2021). RRP: $25.00. Pb, 80pp. ISBN: 9781776564125. Reviewed by Jessie Neilson.

Ruby Solly (Kāi Tahu, Waitaha, Kāti Māmoe) is a Wellington-based cellist, composer, and poet. This is her first published poetry collection, and it draws on her preoccupations with heritage, family, myths and legends, and landscape.

Tōku Pāpā (“My dad”) opens with a prefacing and titleless poem, which firmly states Solly’s allegiance to her Māori heritage. It sets the collection’s tone as confiding, privileging the oral tradition, where knowledge and stories are shared:

‘’When you first told me/about the white man/ I saw him as one great entity/ crushing villages with each step’.

The narrator has grown up aware of political currents, injustice, and intergenerational history. The end of her poem draws right into the personal and individual, of holding her family ‘inside my ribcage’, while also not allowing this closeness to become a prison.

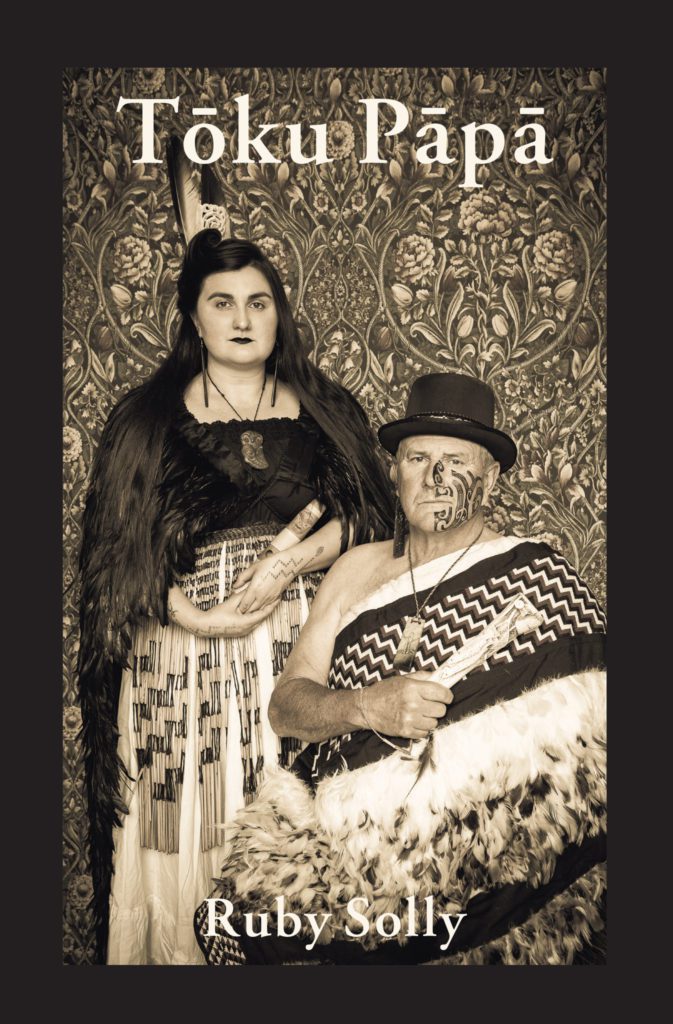

Love for her family permeates these poems, especially for her father, whose presence and guiding wisdom is the main focus. The cover highlights this, as the poet and a father figure pose for a photo, dated, as if from colonial times. The photo undermines the European convention of portraiture, for here are two Māori people, proudly embracing their lineage and traditions, from garb and tā moko, to jewellery, and cradled traditional musical instruments.

Curiously, after setting up a clear defence against colonialism, that subject is mostly abandoned. Solly chooses, instead, to focus almost exclusively on her people and their relationship with the land. Poems are divided into two parts: the first, awe (the essence of the soul; power; downy feathers as on a bird), and the second, kura (feathers; the colour red or scarlet; a glow). The categories are fluid, and the poems could fit into either group, although birds feature heavily in the second part.

The central theme is a young person, learning to negotiate the natural terrain. Her people have grown up harnessing the strength of the land, rivers, forests and sea. She learns from her father how to use a machete:

[I] ‘watch you press it to its grindstone, see the push and pull of preparation bubbling under your skin’ (“The Machete”, p 26).

She, like the other children, learns how to handle the rivers, to be a strong swimmer, dropped into the current by elders. She is proud to be known as a girl who can go with the current (“River Songs-Tauranga Taupō”, p 30).

Boundaries between sea and land merge, and the flame of her father’s cigarette replaces the fading colours on the horizon (“Driftwood”, p 28). Boundaries are fluid too between landscape and person, of tangata whenua, where the living go straight back to the ground. Solly links birth and death, exploring the burying of placentas beneath significant plants (“Makawe-Tuatahi”, p 24), and the digging of graves to honour the newly passed.

She watches her father dig graves, with admiration: ‘when he digs you see it in his body, the flow through the earth into the feet…/and back into the whenua’ (“Six Feet for a Single, Eight Feet for a Double”, p 18).

Interactions with the natural world demand respect. When killing a trout, one must have patience, humanity, and a respect for the sacrifice (“How to Pull a Trout from the River with Your Bare Hands”, p 44). Birds feature prominently, whether in collected pūkeko feathers; the beat of wings and humming of the bush as tīeke, the saddleback, comes charging through; or standing still while a single dove lands on a person.

Many of the poems display pain or hurt, and fear of being swept away by the almighty forces of nature. A poignant sense of being submerged remains:

‘’Under that wet film I was screaming…Then I’d return to the world/even more silent/ than I was before I left’ (“I Dream You”, p 55).

Solly links this to losses in family history, such as tupuna at Gallipoli (“Wairaki”, p 51), like the characters in these stories were mere (teenage) children. Yet she balances this out with positive scenarios from Māori legend: of Paikea riding the waves, similarly voyaging.

Tōku Pāpā is an understated collection, at first appearance quiet. Yet it grows more vivid upon each reading. With this work comes a sense of Solly’s pride, conviction, and knowledge of her heritage, as passed down by her father. She tells of an inner strength, and of a deep respect for the land and its people, and all that both can offer for future generations.

Jessie Neilson

Jessie Neilson holds tertiary qualifications in literature, second language teaching, and library and information studies. Jessie, a regular reviewer for the Otago Daily Times, works in the University of Otago Central Library and has broad interests in matters literary.