More Favourable Waters

THE ANTIPODEAN DANTE

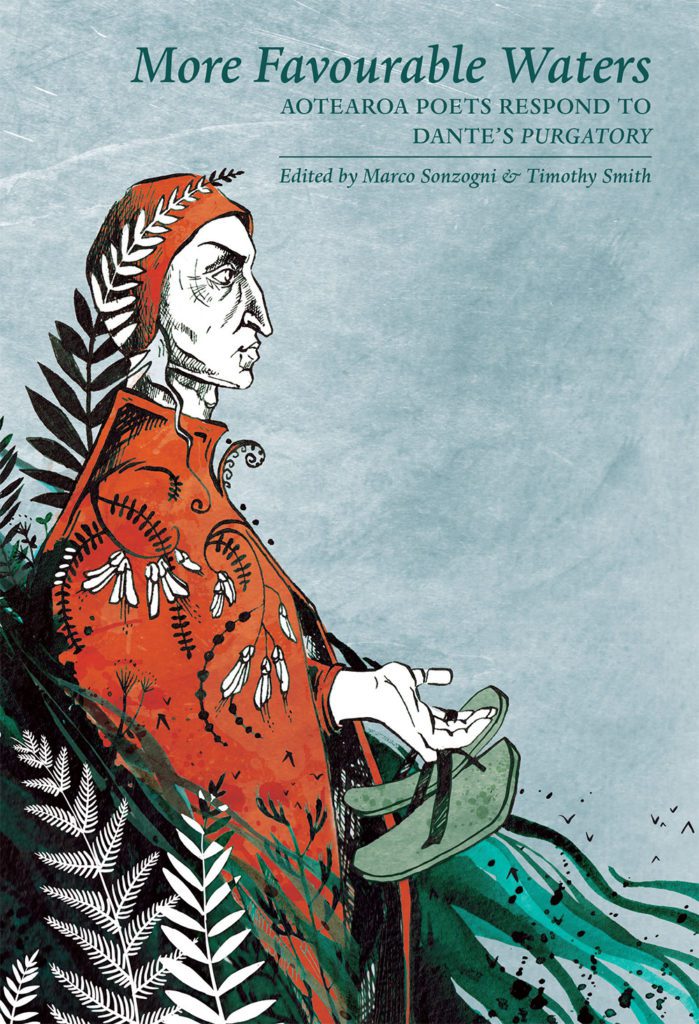

More Favourable Waters: Aotearoa poets respond to Dante’s Purgatory edited by Marco Sonzogni and Timothy Smith. Wellington: The Cuba Press (2021). RRP: $25.00. Pb, 98pp. ISBN: 978-1-98-859535-1. Reviewed by Andrew Wood.

In the 1980s’ reboot of The Twilight Zone, there was a segment called “I of Newton” in which a mathematician accidently summoned a demon à la Faust. At one point the demon quips: “You mention Dante to most people these days, and they ask you how you liked Gremlins.” I don’t think that’s entirely true – there is a general awareness that Dante Alighieri (1265-1321) wrote the Divine Comedy, and some people may have heard of the Inferno, thanks to Japanese anime. But the middle section of the Comedy, one that deserves more love, is the Purgatorio, which has long intrigued me for its Southern Hemisphere hints.

In the Inferno, Dante, guided by the Roman poet Virgil, descends through the nine circles of Hell to find the devil up to his nipples in a sea of ice at the bottom, in the centre of the world (even in the Medieval period they knew the world was round). Virgil explains that when Lucifer fell from Heaven, he fell with such force that his impact created a kind of conical crater – Hell – beneath the northern hemisphere.

Obviously, all the dirt had to go somewhere. Virgil climbs through a tunnel in the ice down the devil’s hairy legs, Dante clinging to his back, only to pop up again on the other side of the Earth at the base of an enormous mountain surrounded by ocean. The missing dirt, Mount Purgatory, is somewhere to the west of the Chathams.

The mountain is inhabited by the souls of the dead trying to work their way up to Heaven. There are no living people in the southern hemisphere, except Dante himself. There is a wonderful passage in the first canto of the Purgatorio that always gives me chills, Englished by me:

Then I turned to the right, I set my mind

upon the other pole, and saw four stars

unseen till now except by the first people.

Heaven seemed to rejoice in their flames:

O northern hemisphere, you widower,

that you are deprived of seeing them!

And I withdrew my gaze from those four stars,

turning back a little to the other pole,

to find the Wain vanished from my ken…

Did Dante know about the Southern Cross? Some Portuguese sailors or Maghrebi traders might have gotten a glimpse of the constellation and the information somehow arrived in medieval Italy, but I doubt it. More likely it is an allegory of the four Cardinal Virtues, Prudence, Temperance, Fortitude, and Justice.

Thomas Bracken’s “Pacific’s triple star” in “God Defend New Zealand” is most likely the three main islands of Aotearoa rather than the Southern Cross, but I wonder if he had Dante in mind and intended a reference to the Theological Virtues, Faith, Hope, and Charity. Aotearoa’s engagement with the Paradisio goes back a way.

If one asked the question, why edit an anthology of New Zealand poems responding to Dante? James K. Baxter got there first and answered it. A prose dialogue by Baxter, (1954) entitled “Dante in the Antipodes” contains the lines:

“Did you ever read Dante?”

“Yes. He put all the people he didn’t like in Hell, didn’t he? And God and Beatrice mixed up together.”

“I’d say he wrote about spiritual states, states of being. You’ve missed out Limbo and Purgatory anyway. All the dry, canny intellectuals went to Limbo. They sat on a green lawn and discussed Philosophy. Inside Hell’s Gate. They didn’t feel any pain. But in order to get to Purgatory he went round and round the Pit, right to the bottom, and came out by a little rock stair in the antipodes. Maybe in New Zealand.”

“I don’t see that Dante’s got much to do with New Zealand.”

“He was a man too. …”

Quite so. Vincent Ward’s 1988 movie The Navigator: A Medieval Odyssey also plays with this trope. Ward’s plague-fleeing villagers from 1348 Cumbria tunnelling through the Earth and arriving in 1980s Auckland, but I digress. Yes, there’s a lot of preamble on my part, but how often do you get to talk about Dante in the New Zealand context?

Baxter and I were intrigued by Dante’s Purgatorio and its Pacific hints. As were Marco Sonzogni and Timothy Smith, editors of More Favourable Waters: Aotearoa Poets Respond to Dante’s Purgatory (Cuba Press 2021), and gathered New Zealand poets to do what it says on the tin: to commemorate the 700th anniversary of Dante’s death.

The 33 contributors all wrote a poem of 33 lines inspired by the constraint of including an assigned passage from one of the Purgatorio’s 33 cantos.

One of my favourite poetry collections, Michael Hofmann and James Lasdun’s After Ovid: New Metamorphoses did something similar back in 1994 with the Roman poet Ovid’s Metamorphoses. Both Dante and Ovid played fast and loose with the themes of their forebears to create powerful and lasting syntheses that are magnificent poems in their own right. It’s a potent frisson that revitalises the experience of reading both the living and dead poet, and these two anthologies both continue that tradition.

More Favourable Waters is dedicated to the late Anglo-Australian broadcaster, critic and poet Clive James, presumably because his final book was a passionate translation of the Divine Comedy in 2013. The passages supplied to the poets are from his translation. It wouldn’t have been my preference, as I don’t think the James version stands up to John Ciardi, Dorothy Sayers, Allen Madelbaum, or even Longfellow as raw material.

The poets in More Favourable Waters are diverse, and the results mixed, ranging from the scintillating to the pretentious. Several participants adopt tercets in a pale nod to the original’s terza rima.

Mary Creswell actually makes it work in her “What poems do in the dark” by repetition and reiteration, recalling the chained poetic forms of the troubadours in much the same way Robert Duncan and Francis Pound did.

Sue Wootton’s “Somniloquy of a somnambulist” very effectively gives a sense of the music of the thing by sustaining the chain of near-rhyme terza rima for a couple of stanzas and bringing in new rhymes as needed.It operates slightly more convincingly than Bryan Walpert’s near-rhyming of the first and third line of each tercet in his “Elegy: Monday morning bus” or Tim Upperton’s “Roadside Trees”, where it feels more forced.

There is often a palpable anxiety of influence among the Kiwis in the shadow of the immortal Tuscan, and his obscure encyclopaedic references, that leads many of the poets to try and sneak around the back way, addressing Dante himself, obliquely or directly, or adopting him as a persona, or even a stalking horse for their own concerns as good poets should.

Michael Harlow looks Alighieri straight in the eye, speaking to him as an equal, or at least, a mentor:

Your songs, Dante.

The shore below

was where I bent

my eyes first…

Of course, Harlow was a grown man when he came to Aotearoa from the US in the 1960s, free of the original sin of cultural cringe, having developed in a literary tradition long since come to terms with Dante as raw materials as seen from T.S. Eliot to, again, Robert Duncan. Here he amicably defers to Dante as guide in echo of Dante’s deference to Virgil.

Helen Rickerby, on the other hand, is not going to submit to what the historian Johan Huizinga once referred to as “the violent tenor of life” in the Middle Ages. In her prose poem “When you fall in love you feel all sorts of sensations inside you, painful and pleasant at once: it is your wings sprouting. It is the beginning of what means to be” she restructures the formulaic tradition of courtly love into a contemporary valediction against unrequited mooning.

Nicola Easthope takes up a similar thread in “On the origins and expeditions of heterosexuality”, deconstructing the crush. That trope of obsessive love and the very un-modern practice of idealising the beloved to the point of apotheosis, is one several poets pick up – no doubt because it seems very exotic.

These days we’d probably call Dante, Petrarch, or Ovid, stalkers. The etiquette being to do that sort of thing in the privacy of our own heads, until we’ve sorted ourselves out. Elizabeth Kirkby-McLeod does this in her “How to remember, how to forget”:

…still my mind tries in vain to think

of just one man alive on Earth today

so hard he’d not have been transfixed by pity

at some loss. If not lions ten moa…

If any contemporary Aotearoa poet is heir to the troubadours and balladeers, it’s David Eggleton, though perhaps more Villon than Dante. I think it’s because his rambling, repetitive verbal tsunamis are as close as you’re going to get to feeling the vernacular, inertial, line by line rolling maul of a canzone without sounding forced and mannered, as here in his “Beatrice”:

She drove her tractor through my field of dreams,

She defragged my every humble brag.

Robert Sullivan’s “Pāua canticle” barely seems to relate to the material but appears to coast off on an impression of the essence, refusing to play the coloniser’s games. This isn’t a criticism, because what Sullivan does is immediately show, in a flash of lightning illuminating the page, the universal humanity of Dante stripped of the historical and geographical context. Sullivan is deft at this, but then he has a genuine feeling for the epic and mythic, choosing instead to adopt an intimate tone more reminiscent of Dante’s Vita Nuova.

More Favourable Waters tells us a great deal about poetry in Aotearoa. Whereas the primarily British and American poets of After Ovid were, more often than not, content to retell the myths with ironic spins and postmodern twists, our poets – a solipsistic lot – bridle from that sort of deference to the canon. The poets in More Favourable Waters seem disinclined to play with the multitudinous mob of historical characters (to be fair, a lot of them are obscure), and the cosmology or theology (likewise obscure) that Dante supplies. Is it colonial cringe? A fear of being misconstrued, by deferring to the European tradition? Is it seen as being too frivolous? Are we too prosaic? Reverse snobbery?

Perhaps that’s an artefact of the poets’ chosen. They tend to lean more to the intimist and experiential than the academic or didactic. Andrew Johnston is in there with “The fall” making damned sure you know that he knows who the White Guelphs were. In many ways, though, the collection was a lost opportunity. I was disappointed that no one, thought to install a cast from New Zealand history on Purgatory’s slopes, not bad enough for Hell but forced to atone for the twined sins of colonialism and imperialism.

While there are poems in More Favourable Waters I like more than others, none of them are duds. It’s a delightful little book, I loved it, and I know just the Italian I’m going to send it to. No doubt it will annoy him.