mō taku tama and ināianei/now

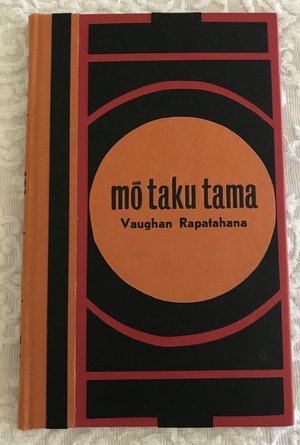

mō taku tama by Vaughan Rapatahana. Kilmog Press (2022). RRP: $38.50. Hb, 32 pp. ISBN: Numbered editions of 50 copies.

&

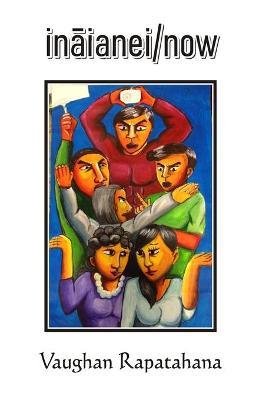

ināianei/now by Vaughan Rapatahana. Cyberwit (2021). RRP: $25.00. Pb. ISBN: 9788182537743. Reviewed by Kirsty Dunn

I cannot cease writing about Blake

In this way I keep him alive

He pātai:

I start by not knowing where or how to. I start by wondering if I should even make an attempt.

I start by acknowledging that I am a mother to a son.

mō taku tama is both a shattering and an almost-putting-back-together again. This collection is a series of questions without answers; a demonstration of aroha and how it feels to fall into the abyss of grief and its undercurrents –- its power, hold, and strange potentiality.

The zephyr that is my lost son / still frisks me;

breezes me with questions I can never reply […]

the zephyr that is my dead son

wafts sometimes right through me […] (“the zephyr”)

A friend and colleague once spoke to me about the kupu “maumahara” (to remember, recall). He said that within this word lies the notion of carrying (mau) one’s pain (hara), one’s sins and transgressions, one’s guilt; that maumahara is a holding of these close to oneself, always. I think about this as I read these poems –- these dedications to a lost son whose memory is held in lines of poetry: the beautiful and the broken. Yet within these dedications and descriptions –- within these memories –- also lie lyrical accusations and harrowing what ifs. These pointed fingers and outstretched palms of poems have words that sometimes step down the page –- that

“P L U N G E” (“I should have done more”) –- to meet their reader, and at other times they contain scattered and broken kupu that dare us to try to reconstruct them. How to make these whole again though, after all that we have read and bared witness to?

they

st utt er here and there

a c r o s s our

stoic walls,

like an affliction

&

they are all liars,

a pastiche of you (“Blake”)

For me, this book is the vessel for the carrying –- the remembering. It is at once a tribute with its handmade cover emblazoned with a golden porowhita sun/son, as the contrasting (and yet complimentary) colours of toto and te pō radiate out and from under it; and it is also a taonga that does what poetry must: it confronts us and challenges us. This pukapuka prompts us to consider the weight of things unsaid, the running out of time, and the blunt thud and echo of loss in the most tragic of circumstances.

In these strange and difficult and unpredictable times, for me these poems to a lost son have something for us all to hold close –- to carry with us.

ngākau pōuri o te huateko

(mō taku tama)

kāore āku mea nui hei tāpiri

he kaipatu te huaketo.

i roto i ngā āhuatanga nui ati i te kotahi

ko ngā tohutohu anake ka taea e au te tuari

koinei:

me awhi tātau tētahi ki tētahi

pēnei kāore he āpōpō

nā te mea ka ngaro tētahi puiaki

me te kore e tohatoha i tō aroha,

he kino ake i te mate ake.

I turn to ināianei / now still raw from the previous pukapuka and note that some of these poems have been included within this collection too. Again, the text confronts me; though this time, it is my knowledge of te reo Māori and English that is exposed and challenged (he kukari ahau).

This collection is divided into sections with works pertaining to ngā whakawhanuangatanga / relationships, ngā wahi / places, te hitori rāua ko ngā aituā o tēnei whenua / the histories and tragedies of this land, and ngā auronga rāua ko ngā huatau / emotions and ideas; however, these kaupapa bleed into and across one another, demonstrating the papa within whakapapa: the layers that connect us to each other and the world around us, and the intricate, complex, and often troubled relationships that constitute these layers too.

[…] the body of my work / is an urupā

remote and elusory. / Feel free to / discover,

drop in & delve, / never forgetting / to s p r i n k l e

your wairua / each time / you clasp shut / the cover […] (“most my books” 143)

Many of the poems are in te reo Māori, and have English language companions –- I am hesitant to call these translations, because to me they are two different poems, each revealing different aspects of the same kaupapa; and each provide, again, various challenges to the reader too. This collection not only traverses relationships between whānau and whenua, but references the piki and heke of trying to make sense of those relationships in more than one tongue and the potent result of the meetings (and sometimes collisions) that occur in our attempts to do that.

I wake up to eat / poetry for breakfast.

choose the words / from a clutter / of cartons / leaningtogether

on the shelf, like students stumbling their first hotel session.

like them, I soon lose / my grip / as vowels / spill the fatigued carpet,

spelling out

auē

auē auē […] (“haven’t had my fill” 138)

A favourite of mine is “ki te tūāriki” [up north]; perhaps it is the northerner in me but the vibrancy and lushness of the memories in contrast to the black words on the white page holds me for a moment; so too, does the cascading phrase “te karera”. The end of the poem feels like an in-joke that reflects the intimacy of the poem itself.

The poems pertaining to Parihaka also stay with me long after reading. In “te hokinga mai a Parihaka” I am at first a little uneasy at the references to taste, to savouring, to the “tart tang” described (p. 48). And then I recall descriptions of the bountiful earth there –- the legacy of the famous māra –- and another layer to the poem is revealed to me; the cultivation of memory, and the strength and flourishing of the people of that place, despite the “agony of history” is what blossoms upon a second reading (p. 48).

These are poems that require the reader to do the mahi; I learn various new kupu here –- in both te reo Māori and English –- as I make my way through the collection. This journey is in equal parts illuminating, fascinating, challenging, informative, and hōhā too, to be honest (“but what does that mean?”). And yet isn’t this also true of the language learning journey? This is a collection I will return to, time and again, as not only a language-learning and playing prompt, but a reminder of what poetry can and might yet do.