Meat Lovers

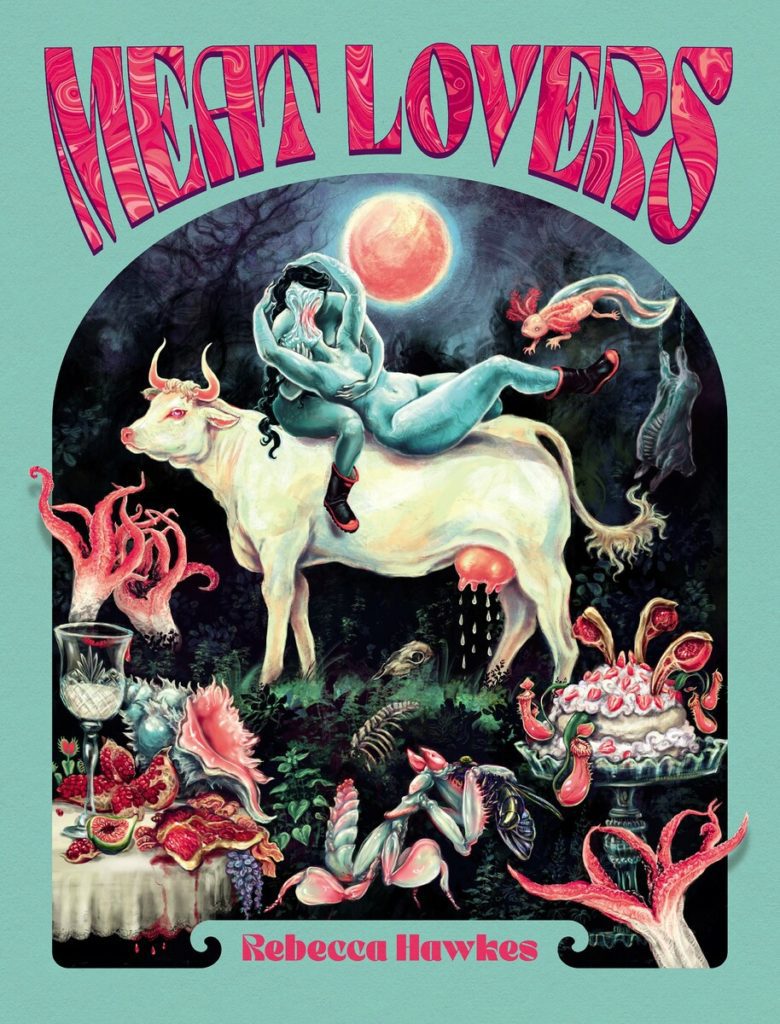

Meat Lovers by Rebecca Hawkes. Auckland University Press (April 2022). RRP: Pb, 92pp. ISBN: 97881869409630. Reviewed by Jessie Neilson

Meat Lovers opens with an ethical quandary amidst a swirling array of the visceral and the grotesque, the benign and the momentary delight. This is the debut poetry collection of Wellington-based poet and painter, and once and eternal farm girl, Rebecca Hawkes. The narrator, assumed to be Hawkes, is standing in the meat aisle of the supermarket, trying to resist the pull of the fleshy slabs. Titled “The Flexitarian” (p. 11), this poem sets up the main motif running through the collection: that of the simultaneous pull towards and resistance from the consumption of sentient beings. With her Canterbury farming background, Hawkes is more than usually informed and aware of the process of a live animal making its way from a field to the dinner plate, and both her horror and fascination are continually juxtaposed.

The first, slightly “fleshier” half of the collection is in fact entitled Meat. We as readers are in no doubt of the topic. The dominant concern is complicity in the killing process and subsequent consumption. However, even in the following section, Lovers (p. 55), farm life and this ethical dilemma rears its head. Lovers expands into a broader discussion of love and care, both towards a particular momentary lover and towards the treatment of other transient beings. Meat and lovers, it seems, are inseparable, both of and returning to the flesh and earth.

Hawkes’ poetry presents varying forms and lengths, but all are free verse. Always she employs non-rhyme. As her madly working mind twirls, so the poems seemingly spill forth. Yet they are carefully shaped as she siphons through her emotions and ideas. Her writing bursts with detail, of the beautiful, the magical, and the revolting. Often this is entwined. She uses similes, metaphors, and personification through which to tell her tales both mundane and imaginative, and alliteration rules the pages. The reader is drawn into the landscapes with a very keen sense of the physical and sensual, as much as we try to pull back and escape.

Dual desires streak through the narrator as she stands in the meat aisle. There is pastoral and cursory care towards other creatures, which she has experienced from farm life in the wool shed and killing sheds, but there is also her burdensome appetite for meat. She sees needle hairs in the meat products, and red ink from the slaughterhouse, reminders of what this product has gone through to become just that. Most horrific for her is the sight of a nipple, staring a ‘pert pink accusation’. Will she ignore it? She stands intrigued, where in her mind

‘Whimpering fat/ melts to breathless squeal’, weeping in the pan, the ghosts of the living creature always present in the room (p. 11)

Later, in the eight-part prose poem, “Flesh tones” (p. 20), the narrator outlines her own, or someone else’s, life growing up as a farm girl. Hawkes adopts a third person voice for distance. Her world, in both passive and active roles, is ‘made on the music of meat’. She reveals her typical ambivalence, where even the graphic process towards a death holds attraction. Peeled possums are strung up as ‘emptying drips’, and lambs being de-tailed experience ‘tower-of-terror ride[s]’. She is drawn towards the lambs in their cuteness and innocence, surreptitiously petting them, for this closeness is frowned upon by other, harder farmhands. She sees the glossy white wool on their tails, which is neatly curled like dried instant noodles. She tries and continually fails to keep clear boundaries between live animal and edible product.

The narrator views all with a pragmatic and gory awe. In an accidental tumbling into a corpse pit she remembers the ‘collateral carcasses’, bursting purple corpses, and rats ejecting themselves in her disturbance. The ‘sweet mordant rot’ is like a backwards vomit. In place of this death of the animate, the inanimate becomes personified: the digger comes alive with its ‘scrabbling claw’ and the pasture is like a bruised human with its lacerated lip.

Yet she cannot halt her thought processes in their morbid preoccupation. Lambs, the future of meat, hop and skip just after ‘burning bone squealed and zipped against scorching iron’, their gummy mouths bubblegum pink. Pain and beauty combine. Furthermore, intriguingly, she places herself within this frame, picturing herself

‘a future consumed/This edible girl. Her fortune of maggots’, where the ‘same savoury singed-flesh stink’ emanates from her own being (p. 22)

A sub-theme is that death is natural, part of the cycle of life. Her school instils this in a young child, on a field trip to a slaughterhouse (“Sighting”). Justified so, our narrator can clear her mind. Death will come to her as it does to other creatures. She is in wonder of the wider world, of the broad Southern landscapes, where she can bask in a river, the

‘meandering progeny of a fading glacier’ (“Noonday gorsebloom”, p. 34)

She sees her ‘wreckage draped with sun-slung nets of caustic light/ her hair swept about like a halo of gilded didymo’

Decomposition is never far away. Once again, the beautiful and the repellent sit side by side. Mortality is acknowledged, yet here it is her own, seen through the eyes of her loyal dogs who believe she is drowning. They are very much alive, powered by their carnivorism, with their breath ‘fragranced with sampled sheep shit and carrion’

Like in the case of the lambs, nature’s adorning one with attractiveness and helplessness is not enough to ward off death. In “The Conservationist ” (p. 30), a tale over eight sparse stanzas, landscape must be rid of predator. Though a litter of newly born kittens huddles ‘so new their irises still glow pale indigo’, they cannot belong, and must meet their end. Here is the moral dilemma physically playing out, where the farmer’s daughter is a

‘turbid mix/ of murder and croon’. Despite cuteness, each is ‘soft furred vermin/ flawless awful/ psychopath in waiting’ (p. 31)

More moments of agency come by in the most disturbing poem, “Is it cruelty” (p. 27). Young people burst through the landscape on the way to a swimming hole, blithe and full of adventure. They come across a sheep with a broken leg and know death is needed, as a show of mercy. However, to bring about death to such a splendid animal, with the ‘noble ridge’ of its nose, its velvety huffs, and its ‘hazel/ iris nebula billowing’, is deeply affecting. They have looked it in the eye as a fellow creature.

There are many instances of hastening death in these poems, as part of the cycle, and witnessed dispassionately by the natural landscape. In “After the blizzard I followed my mother”, the narrator rescues cows, which are part of the terrain, with their ‘obsidian flanks’, where the ‘abyss, gazed back with bovine eyes’. In “Sparkling bucolic”, she helps birth a calf, nature and nurture again intertwining. The wisteria blossoms hang ‘as heavy as udders’, empathising.

Part two, Lovers, likewise bursts at the seams with contradictory stances, echoing the conflicting emotions at the heart and core of an individual. The narrator, or narrators, presents a whole range of possible loves and relationships, the transitory and the more sustained, the reviving and the diffident, and even the toxic.

As in Meat, where the narrator takes on multiple roles, those of nurturer, rescuer, and even killer, here too the lover both repels and attracts, where multiple messages often play out in the same scene. This section adds the theme of make-believe, where she and others are often in costume, or are masquerading in alternative scenarios. Metaphor, simile, fine detail, and other language devices infiltrate these poems.

In one of several play-acting pieces, “I’ll eat you up I love you so” (p. 67), the lover admits to ‘constantly performing violences…/cradling a bottle of/ bleeding heart’, while as a fantastical creature she is ‘an orchid’s deception/new hungers shimmered through my lymph/like treacherous auroras’. Thick with rococo-like detail, this poem is like being lost in the woods in a Shakespearean comedy. She claims: ‘if you are the knife I am the slice’, setting up a co-dependent and needy relationship. Violence, even if only in the mind, often hovers close.

“Werewolf in the girls’ dormitory” (p. 59), also displays lusts and violence, where a werewolf is envisioned subtly wreaking havoc in a dormitory, creeping next to a sleeping female, full of bloodlust, where it could reach out for bodies ‘until they crumple softly…a thrill of temporary/ terrors’. Desire again has tipped over into the territorial and potentially deadly.

In the ten-stanza piece “I can be your angle or yuor devil” (p. 64), a couple in all arrays of costume play at love and tenderness, while ambivalence lies underneath. The innocent and sinister merge in complicated power dynamics, where the narrator has collected hair clumps from which to rebuild the lover if he or she ever leaves, where a ‘blessing is written on the very blades of you’. The body metaphorically is revealed right down to the bone, amongst ‘bleached feather wings’, and rhinestones being peeled from cheeks. Beneath all the pretence, as underneath the cuteness of farm animals, there is little more than mortality, and flesh and bone.

The latter poems in Lovers tend to move away from fantasy, drawing the lens from darkly magical scenarios to those more realistic. However, the imagery remains densely metaphorical. In “Mad Butcher’s love song” (p. 70), returning to a farm environment, Hawkes envisages the primal lust dance between an aristocratic ‘lady’ and a rough farm hand. Death, violence, and sex are intertwined. The farm hand says of her: ‘You sputter and waver like a wick’, in the play of power dynamics. He wants her though he loathes her, as she carves ‘lumpen lovehearts’. She is alternately a shepherdess, ‘cocking your crook, you bad-bitch Bo-Peep’. In their lustfulness, and her ‘breeder fantasies…[an] act perfunctory and absent-minded as a ram’s’, they show themselves as animal, primal, of the land and earth.

Even as we leave the rural setting and approach more urban, domestic scenes, Hawkes keeps us on our toes. Here the poetry often channels a tone baroque, or theatrical, with costume play and love dramas still bloodying the pages. The scenes swirl scarily but full of wonderment.

Some of the other, more realistic pieces focus on a simpler love. “Poem about my heart” (p. 69) is a quiet love song, where love, like life, is fragile. “The salt lamp I got you for your birthday” views the narrator’s love for someone as mirrored by the salt lamp’s sensual qualities. It blooms ‘peach-pink…a spherical lukewarm heart…heavy…a satisfying weight’.

There are moments of tranquillity, of a still love, and they are beautiful. The reader almost longs for this simplicity as a moment of relief. “Because it was hot we stayed in the water” (p. 60), is one such piece, where children, once-swimming in a water hole, are now older, and the scene glazed in attraction: ‘so we stayed salt-caked/shivering/shimmering/ in skins we could taste/just by laying eyes on each other’. Here we have the sensual but devoid of pain or conflict.

The poet and other youthful narrators are constantly hovering in their appetites of hunger and disgust, lust and repugnance. The sensory properties of meat, like sex, both draw them close and frighten them away. The reader shares these predicaments, pulled into situations of uncomfortable intimacy and witness to violence and pain. From the opening poem, where in the supermarket the narrator exhales Hieronymus Bosch-like visions, the reader expects a confronting read. With her richly metaphorical language, where animals and landscape frequently take on human qualities, Hawkes drenches us in her dilemmas. The darkest trough may be “Is it cruelty”, but the reader can never relax.

From the cover of the collection, which Hawkes has created herself, better to keep her vision complete, the reader is tossed into nightmares. Yet, with their deep intelligence, constant questioning, and thoughtful critiques, we find ourselves too easily lost amongst the battering waves of successive images. Layer upon layer Hawkes wields and throws at us, so that we, too, are complicit in her ethical dilemmas. As we navigate our way through these poetic stories, we come away disturbingly unsettled, for what she brings up confirms how each one of us makes choices in defining our brittle lives.