Grand

Grand by Noelle McCarthy. Penguin Random House New Zealand (2022). RRP: $35.00. Pb, 272 pp. ISBN: 9780143776109. Reviewed by S J Mannion

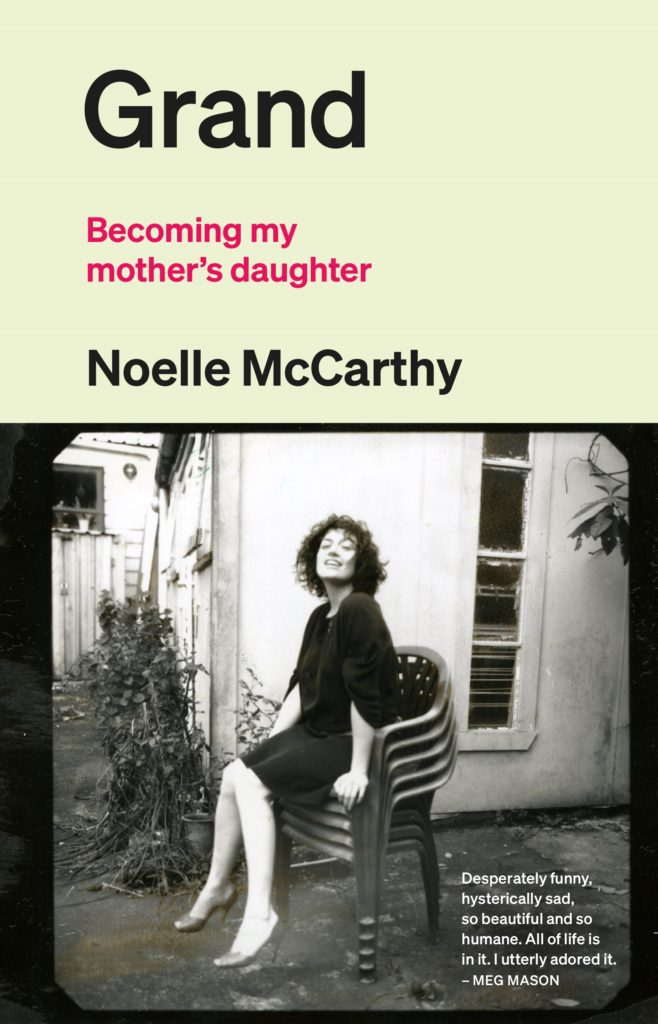

‘Noelle McCarthy is an award-winning writer and a broadcaster.’ She is, and deservedly so. Noelle McCarthy is a very good writer, indeed. This book is a well-crafted thing, yes, both in content and form. The object itself has a sophisticated colour palette and a great cover photo, it is entirely contemporary. Yet for all its style there is also a certain simplicity, an honesty. The narrative voice is clear and clean and graceful. Poetic, in parts, too.

‘Watching her washing through the kitchen window, still deep down in herself, letting the new day gather its momentum.’

(Chapter 6, p. 41)

Neither is it mannered, though it is ordered and structured and so somehow calm, despite its fierce and fractured subject matter. How might that be? To impose a kind of sense on a kind of chaos. Well, isn’t it why we write? Or a large part of it. That and the story of it all.

‘We’ll drink to them now, to Tara and her brother Jonathan.’

(Chapter 4, p. 31)

I felt such ‘kinship’ reading this and I do not use that word or concept lightly. Perhaps, in part, because I too am Irish, and the Hiberno-English of the language is so beautifully colloquial throughout. And therefore, a particular delight to read for any Irish person – a coming home. Abhaile. And no less a delight for the non-Irish, I’m sure, only another kind.

This feeling of ‘kinship’, of connection, of whanaungatanga, comes also because I too am a daughter, and a mother, and a woman. It is quite a female book in that it speaks of and to women, and in being largely ‘about’ the female and the filial. Her descriptions of this central relationship, the one between herself and her mother, this pivotal bond between a mother and a daughter, are very finely drawn, minutely and passionately depicted. I will quote a complete passage here because I think it so perfectly entire and so powerfully emotive. It is rhapsodic, and it is devastating.

‘I would get down on my knees now and climb back up inside her. I am yours, the first one you kept, the one you had at Christmas, I am yours, you bless me each time I walk out of your hallway. I am yours. I love you, you are in me, you are inside me. I hit you I beat you I shook you. I am sorry. I love you Mammy. I knew you.’

(Chapter 27, p. 252)

All through the book there is the shadow of her mother’s alcoholism and then subsequently her own. Their ‘fondness for a drink’ as we say in Ireland, though not entirely without its excitements and catharses, sadly brought more shade than sun into both of their lives. Noelle escaped the worst ravages of it, her mother perhaps did not. Though she was unrepentant to the end.

‘No post mortems, Noelle’, she’d say firmly, ‘it’s too early.’

(Chapter 14, p. 140)

It is both a rending and an uproarious read. Full of that dark mordant wit native to the Irish, but natural to many, humour being both local and universal, of course. I laughed, I cried and then I laughed again. She reminded me of my own mother, and of her mother, and of my own story there. And as many who read this book might well be reminded, of the love we have and haven’t for our mothers, of the mark they leave on us and of the debt we owe them, regardless.

‘You came out of me, she used to scream, you came out of me, you did, ….’

(Chapter 27, p.252)

Yes, we did. We are Matryoshka all.