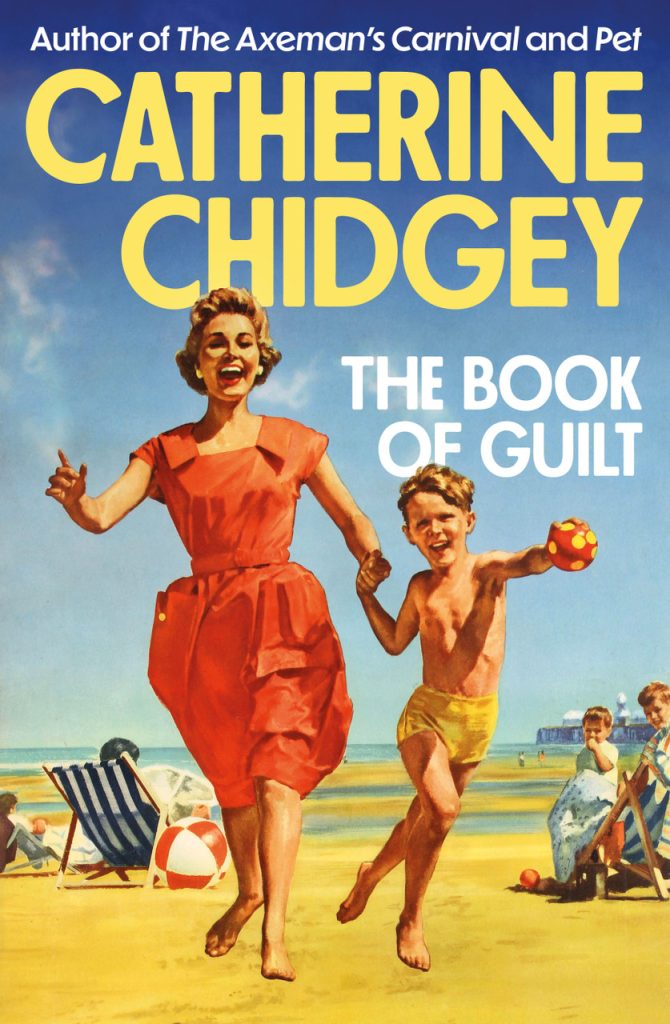

The Book of Guilt

The Book of Guilt by Catherine Chidgey. THWUP (2025). RRP: $38. PB, 400pp. ISBN: 9781776922246. Reviewed by Erica Stretton.

Catherine Chidgey’s ninth novel, The Book of Guilt, was released in May and has already received strong reviews both in Aotearoa and abroad. Adding to the discourse around one of our most acclaimed authors—twice winner of the Acorn Prize for fiction at the Ockham Book Awards, recipient of the Commonwealth Writers’ Prize for Best First Book, and a Women’s Prize for Fiction finalist—is a daunting task. What more is there to say? Fortunately, The Book of Guilt is as rich and layered as you’d expect from a writer of Chidgey’s calibre. Though it marks her first foray into dystopian fiction, it’s an assured and impressive addition to her body of work.

There’s a deep well to draw from in The Book of Guilt for each reader to find their own interpretation, and as always with a Chidgey novel, The Book of Guilt is meticulously researched, its dystopian version of the United Kingdom sinister and dark, giving plenty to chew on. The plot will keep readers turning pages with abandon, and its preoccupation with existential, age-old problems of human nature will push one’s equilibrium just a little off-kilter. Its setting could only be Britain, and these particular characters, only British. The book isn’t dense, or didactic, or pompous, but it runs with fear. Big fears, small fears, and the kind that keeps people within a system from standing up and asking WHY.

Vincent, William and Lawrence are thirteen-year-old triplets who live in an orphanage, a home for boys that is part of the Sycamore Scheme. It’s 1979, an alternative reality 1979 where Hitler was assassinated in 1943 by Major Axel von dem Bussche. After this, the Allied and German powers set out to establish peace as quickly as possible, with bitter choices made to ensure that goal succeeded. Medical research from the concentration camps was shared, and considerable gain came out of penicillin being discovered earlier than in our world. But darkness lurks in the corners. The Sycamore Homes are the brainchild of Dr Roach, who visits and assesses the boys on schedule.

The triplets are imprisoned within the Home. By 1979, most of the other boys who lived within Captain Scott’s walls have moved on, or so the triplets are told, to the marvel that is Margate. A joyous, wonder-filled destination where the sun always shines, and amusement parks beckon. Vincent, William and Lawrence, like every other Scheme resident, want very badly to go there. And to do that, they must be good boys.

Their lives are circumscribed: no television, no news, no contact with the outside world. Anything ‘bad’ that they do is written down in the ‘Book of Guilt’ and their dreams are inscribed every morning in the ‘Book of Dreams.’ If they want to know anything, they consult the encyclopaedia, the ‘Book of Knowledge.’ Every child who has been in the Scheme also has the ‘Bug,’ an illness that comes and goes with different symptoms for each child. Ostensibly, Dr Roach is working on a cure for the triplets: ‘he travelled abroad, sharing his work with other doctors in the hope of curing the “Bug.”’

But the Scheme is winding down, at the behest of the Government; the Homes are emptying. The prison-like conditions the boys are kept in are changing. Small, shabby changes that act like tremor cracks in the triplets’ existence.

Both plot-driven and ideology-focussed, The Book of Guilt will appeal to many. Not a word is wasted, and not a moment stretched beyond its limits. Three voices tell the story: Vincent, one of the triplets; Nancy, a child in the community with parents who, for reasons unknown, lives a similar constrained life to the Scheme children; and the Minister for Loneliness, a new position in the government, whose voice is perhaps the most necessary as it shows the outside world and the politics that got the country here. This voice, sometimes, has the least appeal, but Sylvia does illuminate the role of women in a society where they are only just beginning to occupy major public roles, roles where they’re required to be rock hard, unflinching, and also conform to acceptable standards of beauty.

Chidgey presents a Britain that is unsettling in its similarity to the ‘real thing,’ with Spirograph, fish paste, the reported seaside delights of Margate, and the unnerving mention of the TV programme Jim’ll Fix It. Having published two novels set in Germany during World War II, The Wish Child and Remote Sympathy, to reimagine the United Kingdom into a state where some of Nazi Germany’s ideals have penetrated local consciousness feels almost an inevitable extension. As the book explores collective amnesia, and the ability of individuals to ignore what’s under their noses in the pursuit of self-preservation, we’re reminded that perhaps we don’t know how we would react in these circumstances.

Kazuo Ishiguro’s Never Let Me Go is a natural comparison for The Book of Guilt. Both set in the 1970s, in a boarding-school style home where the inhabitants slowly realise that they are different, so different, from everybody else—there are definite similarities. The Guardian review of The Book of Guilt, however, points to Ishiguro as differing from Chidgey in that he ‘does not seek to rationalise or explain the world in which the book is set. His interest is personal, not political’ (Clare Clark, 2025). Yes, The Book of Guilt does look wider into the political context with the two exterior points of view (Nancy, and The Minister for Loneliness) but it also has a personal beat: at its heart it considers a deeply intimate and complex relationship—that of three brothers with wildly different personality traits, testing how far they will go to maintain, destruct, or cling to those bonds.

It is to Chidgey’s credit that she can speak to the same theme internally and externally in the same book, laying down the ground she wants to explore on both personal and political levels. Combined with a compulsive moving plot, The Book of Guilt is a must-read.

Erica Stretton is a writer, editor and reviewer from Tāmaki Makaurau. She has a Master of Creative Writing (First Class Honours) from the University of Auckland and was awarded a 2024 Surrey Hotel Residency. Her fiction has been published in Headland, Mayhem, Flash Frontier, ReadingRoom, and takahē.