Slowing the Sun

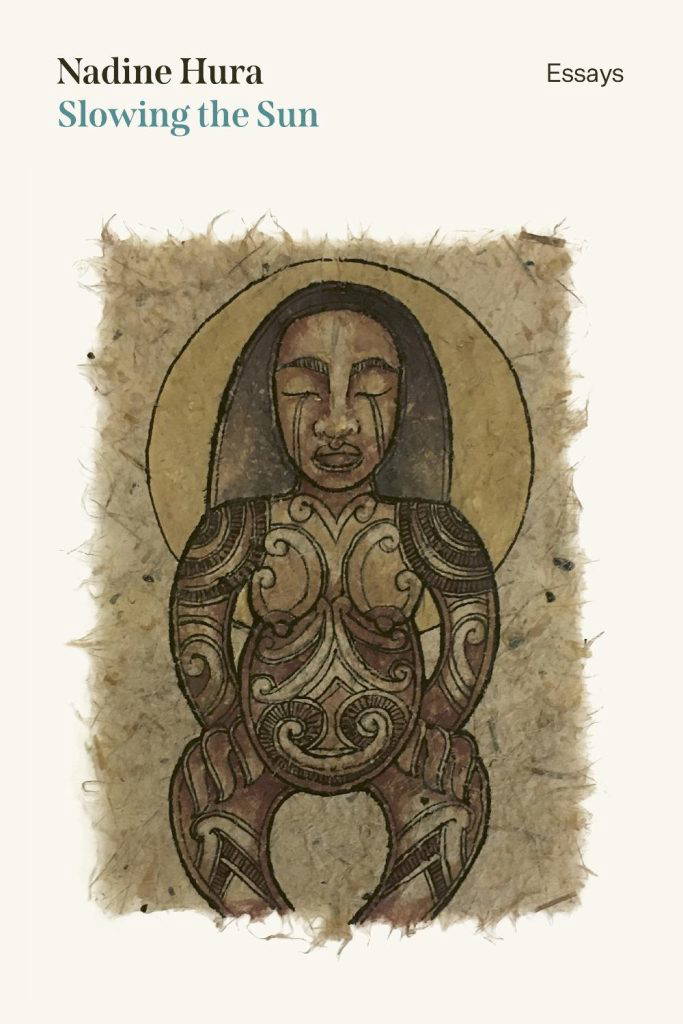

Slowing the Sun by Nadine Hura. Bridget Williams Books (2025). RRP: $40. PB, 240 pp.

ISBN: 978199130169. Reviewed by Māia Te Whetū.

Nadine Hura’s Slowing the Sun is the kind of book you have to put down for a few days once you realise you’re nearing its end, when the pinch of pages between the fingers of your right hand is getting thin, and you can feel the poroporoaki approaching. Wildly informative and generous, Slowing the Sun begins as an inquiry into the world of climate change activism and swiftly unfolds into an interrogation of the racist hierarchy of knowledge. These essays welcome us into conversations being had in the margins, about our relationship with the natural world and the abundance of mahi that is dedicated to protecting that relationship. Each essay is committed to revealing the interconnectedness and whakapapa of all that is before us, offering rich details of the author’s experience to deliver a truly phenomenal collection. This is perhaps my favourite read so far this year.

Hura cleverly introduces the collection with an essay detailing her own frustrating entry into the arena of climate science. She recalls attending swanky climate conferences and being exhausted but not totally surprised by the relentless prioritisation of an objective and detached analysis of the climate crisis, while carelessly neglecting indigenous bodies of knowledge. We are invited to consider the type of knowledge that is legitimised by western scientific standards and how this knowledge may be used and shared. What is lost when mātauranga Māori and the ancient knowledge that can be found within pūrākau is at best undervalued and at worst suppressed? With these first few essays, the author revives the stories underneath climate statistics, or rather, brings forward the lives of people who are living in the consequences of such statistics. The world of climate science is made digestible and personal here, as it has always been in te ao Māori. As readers, we are consistently reminded that the fight for our natural world is inextricable from the honouring of Te Tiriti and the enduring struggle for Land Back:

‘For Māori, this is not a new crisis but a continuation of a long struggle. The forces that have led to urgent calls for action on climate change in 2019 are the very same ones Māori have been protesting and resisting for generations.’ (‘Who gets to be an ‘ordinary New Zealander?’)

‘Statistics are just stories without faces.’ (‘Pathways to freedom’)

Slowing the Sun introduces us to pockets of resistance across the motu in small communities that live in deep connection with their whenua. Among them, we meet teenagers at Taita College in Lower Hutt who are removing gorse and replanting harakeke. Together, they notice the butterflies returning to the area and the creek running freely. We meet Hank Dunn from Pawarenga who has survived five shipwrecks and knows the rising sea levels of his coast intimately. While these stories showcase the meaningful mahi being done in our communities, they also investigate the ways colonial violence has strategically intercepted possibilities for such mahi.

Through explorations of personal grief, Hura delicately weaves the threads of our severed relationship with the land, ourselves, and each other, and in doing so exposes the personal everyday consequences of the destruction of our whenua. How do our bodies experience this destruction? We are reminded of this most poignantly in the powerful account of Hura’s brother, who is failed by the same colonial violence that degrades our whenua. This collection confronts the reader with countless cases of insurmountable loss. Loss of land, knowledge, skills and the people and places we are tethered to. Hura’s essays are saturated in grief and buoyed by connection. I was often struck by an overwhelming wave of pain that was being recognised in these pages, which was sometimes soothed in the next few, and at other times left to stick. As Hura notes, ‘[…] just because it is beyond climate science to show precisely how these disparate events are connected does not mean that they are not.’ (‘Holding back death’)

Not quite ready for the words to run out, or perhaps not ready to be alone with what I had read, I had to put Slowing the Sun down to let it simmer. When I returned to the book after a few days, a short and profoundly moving chapter focussed on Moana Jackson swelled with sentimentality. Featured in this essay was a letter Hura received from Moana, expressing his respect and admiration for our indigenous creatives. We are welcomed into an appreciation for art as resistance and cultural preservation, for the creativity and innovation innate to te ao Māori and our poets and artists who unveil this world and imagine worlds beyond it.

Hura’s words are rhythmically crafted, using language so precise and sensory that we are pulled into affect in surprising ways. I was initially surprised by the frequent linguistic investigation throughout the essays, but then realised, of course, the author is interested in the whakapapa of a word. The fascination of how words can be transformed, the kinds of relationships one word may have with another and the curiosities of language are most profoundly explored in the essay ‘A Wreters Legacy.’ Prompted by Hura’s time as a writer in residence at the Michael King Writers Centre, this essay revealed the most to me about Hura as a poet, as she marvelled at the life of Barry Brickell, his dedication to the natural world around him and his playful aversion to the literati. Throughout the collection, but in this essay particularly, Hura’s writing is permeated with an inquisitive awe that is entirely contagious.

Generous with insight and intimate kōrero, this collection sparked an indomitable inquiry into the whakapapa of just about everything around me and how it came to be right here. I’ve come into a good practice of questioning where things come from, but this collection accelerated this practice into an irresistible urge. Since finishing Slowing the Sun, my walk home from work has been permeated by thoughts of who’s ground up maunga I might be walking on, and how far I may have to look back to see it standing whole again.

Māia Te Whetū (Waikato Tainui, Ngāi Tūhoe) is a takatāpui writer and bookseller born and raised in Ōtautahi. She spends most of her time in the company of the moana, her whānau and growing stacks of books. Her work can be found in takahē, Awa Wāhine, Starling and Moana: Voices of Our Ocean published by Tagata Atamai.