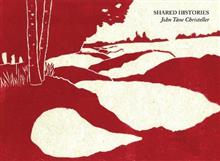

Shared Histories by John Tane Christaller.

Shared Histories by John Tane Christaller. The Cuba Press (2022). RRP: $30.00. Pb, 50 pp. ISBN: 9781988595597. Reviewed by: Sarah Maindonald.

When I first perused this collection, I was hopeful. It seemed a noble task to try and capture our ‘shared histories’ and give profile to some of the most tragic and sacred sites in Aotearoa. In Christeller’s slim but intriguing selection of woodblock prints and associated poetry he was hoping to impact us in the way that Kay Walking Stick, an indigenous artist from the Pacific Northwest, had impacted him.

I was curious, who was this man? Who were his people? What iwi did he come from? Who had given him the name of Tāne? Who were the kaumātua standing behind him, how did he address cultural safety, whose histories were ‘shared’, or was this just a ‘muted response’ (p.9) to our history of colonial oppression?

I have to say I am conflicted between appreciating the simple appeal of these artworks and their accompanying poems, devoid of people and their focus on the concrete – fences, gates, and tentative references to racial division and on the other hand feeling somewhat deprived of the people’s history – where are the stories of tangata whenua between the fences and gates, where are the realities of the tragic losses scarring the memories of Tuwharetoa, Ngai Te Rangi, Tainui, Ngāti Whātua, Ngā Puhi and many, many iwi across Aotearoa. Whose stories are these to tell? There is mention of only one kaumātua from Ngati Rangitane that I could identify as any kind of cultural consultant. I wondered where the shared voices were in these narratives? This created a cynicism towards the notion of shared histories, as we are presented with these ‘histories’ through a tauiwi lens with limited accountability. I was reminded, however, of aroha ki te tangata and the positive intention behind these works.

Te Uru Karaka (p.10) gives a perfunctory history in English:

…iwi jostled for space in pre musket days,

Rangitane and Ngati Apa

On Te Motu o Poutua Pā

Where mainly women and children were present

The second followed at Te Kairangi

A traditional man to man battle

Where Linton camp now stands

Ngati Apa were vanquished.

The grove of solace with war-aged trees

commemorates both battles

a grove to which I often walked to eat my lunch (p.10)

Yet there is something missing in this account, it feels a bit too mundane, ‘a place to eat your lunch’ and yet for a place imbued with such huge history it is given sparse description indeed in a mere eight lines. One might question even the mention of kai in the evocation of such a tapu site. The translation of this in te reo seems to harness a little more empathy, he describes Te Uru Karaka as he uru pōuri, using pōuri to capture the English word ‘dark’ but in te reo it is often used to mean also, a darkness of the soul, gloom, despondency, sadness. One would hope this was deliberate … but it is ambiguous.

Words used like ‘hangatanga’ instead of ‘whare’ in talking of whare wānanga, also raise questions, not that they are incorrect but do they illicit the sense of authenticity the writer is presumably aiming for? I’m not sure. Later in the poem he speaks to the battle at Te Kairangi, kanohi ki te kanohi, ā, i hinga a Ngāti Apa. This use of reo in this section feels more familiar, and carries a more authentic sentiment. Rangiriri (p.29) continues this matter of fact tone:

A few ancient grooves in the earth,

A waharoa of indeterminate age,

Recent but not contemporary

And lacking a path both to and from the archway

So is this enough? Is it a privileged position to hold, to choose to have a ‘muted response’ to a site that has such a history of pain? Where lives were lost, homes burnt, women forever injured, whakapapa profoundly impacted by the intergenerational trauma stemming from this event? Or is this an invitation to populate this picture with the people in our mind, to see the history, to feel the wairua of this land, itself?

I would encourage those diving into this dilemma to take up the challenge Christeller extends, and to explore the layers of history which populate these sites. These artistic creations can offer a window into our past, regardless of who is holding it open.

Disclaimer: Despite 40yrs engagement with Te Reo, I consider myself a learner, and not a native speaker. I don’t whakapapa as Māori. I wanted to acknowledge this, so as to not claim authority in this area but to offer a response.