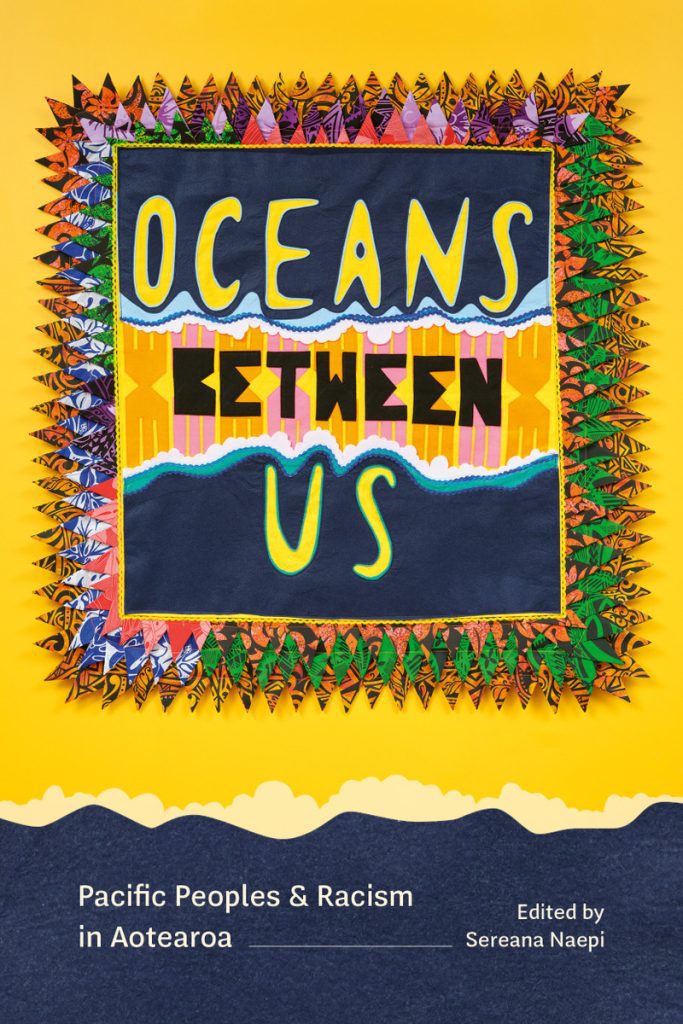

Oceans Between Us: Pacific Peoples and Racism in Aotearoa

Oceans Between Us: Pacific Peoples and Racism in Aotearoa edited by Sereana Naepi. AUP (2025).

RRP: $40. PB, 272pp. ISBN 9781776711253. Reviewed by Tracey Sharp.

We know the statistics. Pacific peoples in Aotearoa consistently rank lower than non-Pacific populations across nearly every measure—health, wealth, home ownership, longevity, educational attainment, and wellbeing—and higher in incarceration rates. And what we also know, but is less widely acknowledged, is that New Zealanders have a long-standing problem with accepting the causal story, the why, behind these statistics. Oceans Between Us: Pacific Peoples and Racism in Aotearoa confronts this reluctance and challenges prevailing narratives across its ten chapters in this collection of essays.

Editor Sereana Naepi (Fijian, Pākehā), an associate professor of sociology at Waipapa Taumata Rau, brings together critical academic analysis and lived experiences of thirteen Pacific scholars to dismember the body of a lie: that Pacific underachievement is a personal or cultural failing, rather than the predictable outcome of a system never built for them. This is not a call to dwell on yesterday but a compelling argument that we cannot simply ‘move on,’ because the past is not behind us: it is still unfolding in the present.

Most New Zealanders prefer to believe it isn’t racism—that ‘unhelpful’ word, to borrow from Chris Hipkins—at play. And let’s not even try to discuss structural racism—cue national eye-roll—the notion that racism is foundational to Aotearoa New Zealand and continues to marginalise, constrain, and extract from Pacific peoples while insisting the system is fair. As the editor notes, ‘the world that we inherit and exist in [is] shaped and determined by its histories.’ Demonstrated throughout the collection is just how history has shaped key structures—economy, education, migration, health, and climate justice—in ways that reproduce discrimination, inequality, and injustice today.

In the chapter titled ‘History: “They Call Me A Bunga,”’ contributor Marcia Leenan-Young takes on the impact of colonialism, addressing the denial of racism in New Zealand and laying bare the circular connection between racial stereotypes and systemic racism: racial stereotypes justified the way the system was built, and the system then perpetuates those same stereotypes by excluding Pacific peoples from opportunity, in favour of those the system was built to serve.

‘Economy: Is the Migrant Dream a Capitalist Dream?’ is one of the collection’s most thought-provoking, probing what may be the book’s knottiest problem: capitalism’s structural reliance on exploitation. By design, capitalism produces winners and losers, making inequality ‘an unquestionable reality of modern society,’ where ‘somebody’s going to be exploited for capitalism to survive.’ And it’s here that capitalism and racism converge: ‘Racism is foundational to capitalism. Capitalism is predicated on the exploitation of labour and resources… Indigenous bodies and land are exploited in order to benefit a settler state, its settlers and their descendants.’ Concrete examples follow—from land theft and the Pacific pay gap to the mechanics of Recognised Seasonal Employer (RSE) schemes and the rollback of redistributive tools like Fair Pay Agreements. Yet authors Sereana Naepi, Lisa Meto Fox, Dylan Asafo and Evalesi Tu‘inukuafe pose a tough question: can policy mechanisms that target inequity also uproot racism? If not, they argue, mere inclusion in an unfair system is hardly justice. The discussion is so richly layered it could easily stretch into a book of its own.

Subsequent chapters dissect the genesis and effects of structural racism across key domains: education, migration, climate justice, health, higher education, and the justice system. Written sometimes by individual authors and sometimes through shared talanoa, and drawing on both critical theory and personal storytelling, each chapter serves as both a standalone dissection and a building block—contributing to a fuller understanding of how structural racism shapes policy and praxis, and how this impacts the lived experience of Pacific peoples.

The fusion of academic theory and language with Tautalanoa—‘to speak straight, to address a topic with the necessary layers of knowledge’—offers a powerful response to foreword writer Ashlea Gillon Aramoana, who issues a karanga for the authors to speak, discuss, and share: a call to ‘disturb the dust’ and have ‘critical, direct conversations about the many promises that New Zealand has broken for Pacific peoples due to racism.’

Although a more rigorous edit could have reduced some overlap between chapters and clarified overall intent—particularly in the ‘Education’ chapter, which veered in too many directions to present a bold, coherent case, these are minor quibbles and don’t detract from the power of the whole. Each chapter ends with proposed actions, such as improving access to data, reforming funding structures, and acknowledging our shared history. And there are, if not answers, responses, ideas on how to challenge the status quo.

There are also important, timely and complex questions to wrestle with. What would it take to overcome historical structural disadvantages, given they are baked into the capitalist system? How can Pacific peoples prosper in a society that still has deeply ingrained racial prejudices and believes in these stereotypes? Will economic redistribution via policy adjustments deliver on Pacific aspirations? Do Pacific peoples truly wish to be integrated into the exploitative, capitalist, system?

In the closing chapter, ‘The Next Generation: To Weave Dreams of Liberation,’ Chelsea Naepi states that the task in front of the next generation is ‘to step into these unknowns.’ And just as Epeli Hua’ofa saw the sea as an ‘open and ever-flowing reality, [where] oceanic identity transcend[s] all forms of insularity,’ so too must the next generation ‘use love as a revolutionary tool of liberation for not just us but all marginalised peoples.’

Written for anyone who wants to understand the roots of Pacific disadvantage, Oceans Between Us is equally a rallying cry to Pacific peoples themselves. As Marcia Leenan-Young insists, ‘the history of stereotypes is not a true reflection of our peoples,’ and so knowing that history is therefore the first act of resistance.

In a political moment when ‘equal treatment’ rhetoric attempts to erase the reality of inequity, this book matters. The stakes could not be higher. If we acknowledge structural racism, then policies that rectify the unearned discrimination that holds Pacific peoples back from fulfilling their potential would not be ‘racial discrimination’ (thanks, David Seymour), but would be understood as necessary and fair. And New Zealanders love to think we are fair. Oceans Between Us: Pacific Peoples and Racism in Aotearoa challenges us to prove it.

‘There’s more than enough. There’s more than enough for everyone to have a decent home that they can live in, to have decent food, to access the doctors. There’s more than enough to go around.’

Tracey Sharp is a writer and researcher of Pākehā/Fijian descent based in Tāmaki Makaurau. She holds First-Class Honours Master’s degrees from the University of Auckland in Sociology (2017) and Creative Writing (2021/2022). As a project manager for the Going West Trust, Tracey is spearheading an initiative to restore and transform Maurice Shadbolt’s former home into a vibrant new writers’ residency in Titirangi. She also facilitates creative writing workshops at the Ōwairaka Community Club and is an active advocate for greater income equality and social justice in Aotearoa New Zealand.