Hoods Landing

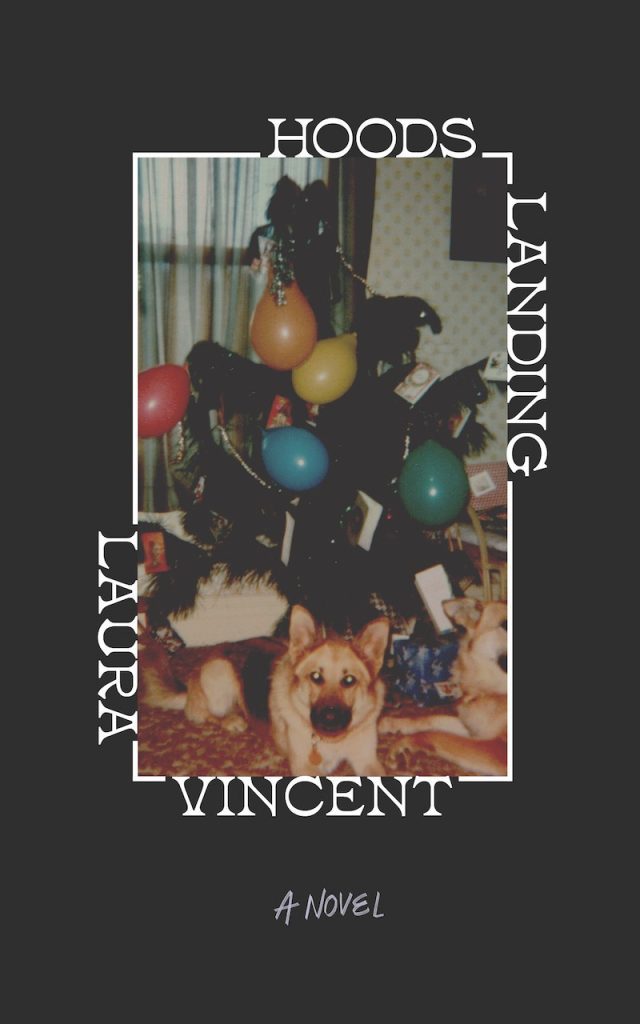

Hoods Landing by Laura Vincent. Āporo Press (2025). RRP: $35. PB, 256pp. ISBN: 9780473745684. Reviewed by Laura Borrowdale.

Laura Vincent’s Instagram, @hungryandfrozen, used to be full of bird’s eye images of delectable plates of aspirational food: pasta with harissa and beans curled lovingly on a pea green plate, mint choc chip ice cream with a scoop missing, ginger kisses on a wire rack. Recently, however, the account has veered sharply away from food and into something altogether different and, depending on your appetite, more interesting.

Vincent, a food blogger and cookbook writer, has turned her attention to fiction, producing Hoods Landing, a darkly funny and profoundly domestic exploration of the ways in which families operate: both the stifling and the support.

Hoods Landing begins and ends with Rita, or ‘Baby Ree’ as she is known by her older sisters, as she contemplates how to tell her family about her recent cancer diagnosis. The women of the family—because this is a book full of women, their men either merely background noise or relegated to the past via divorce or death—Marlon, Judy, Jayne and Rita, arrive with their various adult children to celebrate Bufty, their mother, on her birthday. Rita waits and waits to make her revelation, as she ‘knew you couldn’t expect to hear secrets in broad daylight. They came out later.’

The family of Hoods Landing seems to recall a previous era of writing: the era of The Darling Buds of May or Nancy Mitford, writing in which boisterous but kind families have tumbled over and around each other like river stones for long enough that their sharp edges have mostly been knocked off. Vincent writes that during the times the family reunites:

‘The songs stayed the same, the food stayed the same, the plates and bowls and cups were the same, the same conversations, the same tensions papered over in the same ways, and this could comfort or suffocate, cause onlookers wild jealousy or stultifying boredom and it would always be the same, and by the time it had changed, it would be impossible to work out when this change occurred or to which part of the whole.’

There is a reassurance throughout the book of a gentle returning to centre, or continuing to be, that the matrilineal family seems to provide, one woman taking up where another left off. These are women who, through generations and across the mortal divide, return to care for one another, and Vincent assures us that the dead are with us over and over again.

Between these family occasions, the mystery lying at the back of Hoods Landing is revealed through the alternating chapter structure. Switching between the family scenes and a series of cancerous deaths of women in the area (‘at least ten,’ which the main character, Rita, thinks might be a ‘normal number of women to die’), Vincent hints at something darker and more menacing, an undercurrent that never quite comes to fruition. There are mutterings early in the book about possible reasons why these women are dying, that it might be ‘whatever Murphy’s spraying out there,’ or the ‘lead pipes and asbestos ceilings’ at the school that the government never got around to replacing, but ultimately what really matters here is the family.

The women of Hoods Landing are warm and generous, and equally take no bullshit. They are a family obsessed with food, a trait that takes advantage of Vincent’s clear foodie tendencies. The novel’s ‘ladies, a plate’ era means that each woman arrives at each event with a plate, and Vincent’s love for food is easily apparent.

‘Anyone could’ve told you with eyes shut what food they’d eat: Marlon’s potato dish; a roast chicken and Bufty’s bread, its cozy scent reaching out to greet you; Judy’s rice salad; Rita’s tabbouleh, flecked with mint and parsley from the garden; splintered wedges of Sissy’s spinach and mushroom filo pie; minted new potatoes; sliced cucumber in white vinegar; tomato wedges, red as the approaching sunset.’

Vincent’s eye for the sharp detail lifts it sensuously off the page, and as the book centres around various family celebrations, there are many occasions for food to do some of the heavy lifting of the women’s characterisation. The exploration of the domestic and the elevation of the home as a site of something interesting and dynamic is refreshing.

The promotional material promises elderly lesbians, twins and dogs named Roger in a way that seems to belie the real strength of this book. Suggesting these elements are played for laughs is at odds with the deeply considered, gentle and richly explored lives and inner worlds of these characters, and the honour Vincent accords each character, their foibles and eccentricities making them real, rather than jokes. In this novel there is a deeper purpose: the revelation of the rich and interwoven lives of women, as sisters, daughters, aunts and grandmothers, as ancestors.

Laura Borrowdale is a writer, reviewer and educator in Ōtautahi Christchurch. Her second collection of short fiction, Dead Ends, was recently released with Tender Press. She is one quarter of ngā pukapuka pekapkea, a micropress specialising in chapbooks.