Dear Alter

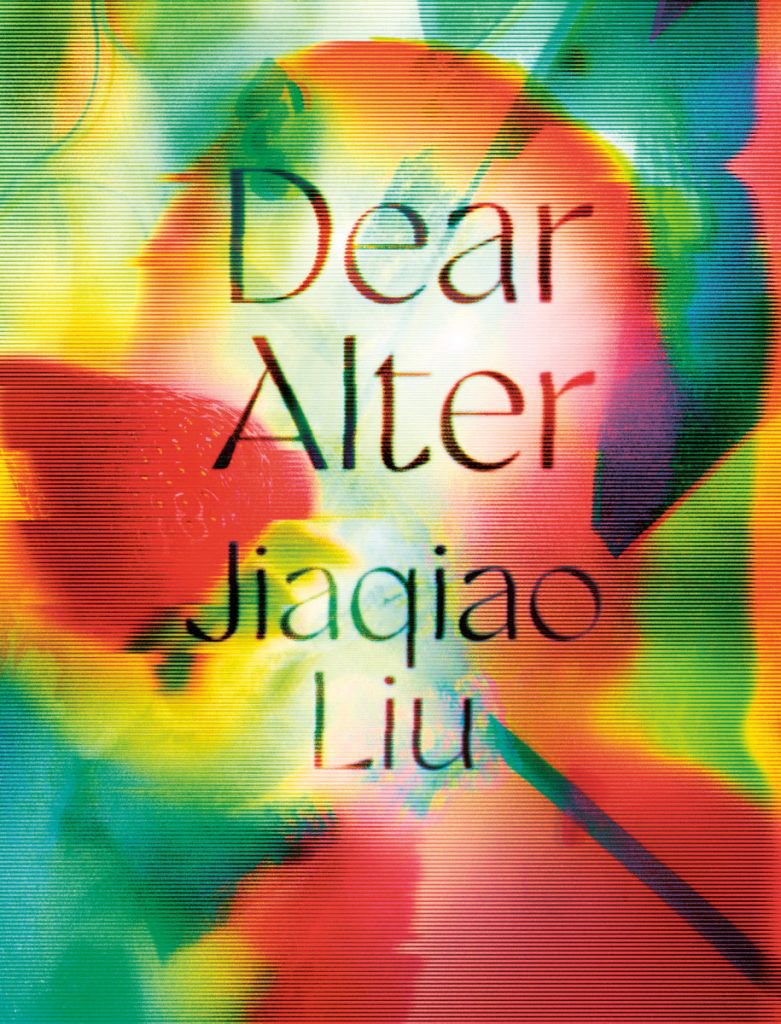

Dear Alter by Jiaqiao Liu. AUP (2025). RRP: $30. PB, 116 pp. ISBN: 9781776711697. Reviewed by Dani Yourukova.

I am on a long distance call, sloping about the kitchen in my socks, when I notice that my mum uses ‘he’ pronouns for ChatGPT now. She’s annoyed because I made her feel guilty about the environmental impacts of GenAI last time we argued. Now, we are arguing about it again, across 17,000 kilometres of ocean. It feels too convenient, arguing about AI gender in the middle of reading Dear Alter. I hang up. I go back to work.

I first read a draft of Liu’s debut collection in 2021, when we were in an MA programme together. Approaching it this time round, I was afraid that I might find a shriveling of my own emotional capacity to re-enter this world of artificial intelligences, given, you know, everything happening right now in the tech space. Luckily, Dear Alter has such a sophisticated and multivalent voice, at once wise and vulnerable on its theses of otherness, gender, intimacy, grief and distance, that dipping back into its electric currents comes easily. Though easy isn’t necessarily a word I would use for Liu’s intense and enigmatic collection.

‘INTERIOR CLOSED TO THE PUBLIC AS OF NOV 2019 & MAY NEVER REOPEN,’ the first poem of the book declares boldly, which is not the only title that seems to be working to hold the reader at arm’s length. Many of the titles are formal, detached, and bordering on academic: ‘Telenoid-mediated conversations in an elder care facility,’ ‘Inorganic Carcinisation in the Neo-Cambrian Era.’ Others declare themselves to be one-way communications from a variety of desolately lonely places: ‘transmissions from an empty museum,’ ‘fragmentary transmission from the end of the world.’ Often, the first thing the poem does is make you conscious of how far away you as the reader might be from the speaker, or how difficult it is to find a connection point between you, regardless of whether you’re crossing an apocalypse, or the white space on a page.

Though the bodies of these poems move evasively and with subtlety, always they work to close the distance. In ‘INTERIOR CLOSED TO THE PUBLIC’ for example, the initial distancing continues through the first stanza, which we find is in the voice of an impartial observer:

‘some forms of flux are considered finished states

or at least, metastable. dissociation

of the atomised self. swapping parts

down at the body shop, hip-mod out

triple-joints in.’

At first, the narrative voice stays firmly in the realm of abstraction. Who might be speaking, and whether they are referring to themself or something other, is made both ambiguous, and negotiable. When you can swap parts down at the body shop, at what point does one body end and another begin? But these are not quite human bodies as we know them. Where we might expect to find mention of flesh or bone or hair, there is triple-jointed chrome, and where we might expect to find an essential self, we find many possible options. It’s destabilising, distancing even, to have the body you know pulled out from under you and replaced with a machine. But the poem soon shifts from the detached voice of the technician into the voice of the storyteller:

‘at the end of the world

the oldest soul got put in a baby

and baby got given a box

full of gender, and, y’know, children

are scientists, and you can never say

you are allowed one toy and one toy only’

Without changing from its position as the voice of an outsider, the poem draws quietly closer. We are given a more familiar visual, a more recognisably human entity (though still the boundaries between self and other are complicated by reincarnation), and correspondingly simple language. We even get a conversational ‘y’know.’

By this point, I find that I’ve softened on the voice of the detached scientist and the machine body, whose relationship to the child in the image slides carefully into place. How like a child to observe a world it doesn’t entirely recognise! And how terrible to deny our most curious selves the possibility of change.

By the final line of the poem, all this mingling closeness has resolved into a first-person pronoun as the voice admits it has a personal stake in the matter.

‘I began to see what ate at me.’

Having done the work of moving gently and attentively through the poem, suddenly you are holding a little machine heart in your hand, whirring in a language that is almost (but not quite) beyond you.

Language and isolation are common difficulties for Liu’s tender machines, holding them just slightly apart from the worlds they inhabit. In ‘mummy’s little robot,’ a small machine cries for its ‘ma,’ in a manner just slightly developmentally atypical for a child of its age:

‘小ROBOT never cries

in alarm or distress, only

in mildly perturbed but perfect

American English.’

This machine, we feel, is loved. Its mother ‘comes running’ when it cries. But there is difficulty too, in the language between 小ROBOT and its family. We might imagine a gap in language implied by the mingling of untranslated Chinese characters and ‘American English,’ but also in the way that 小ROBOT doesn’t know to cry like a ‘normal’ child.

In ‘Inorganic Carcinisation in the Neo-Cambrian Era’ the character of 小ROBOT returns, now at the bottom of a post-apocalyptic ocean, where its isolation seems to be complete.

‘小ROBOT woke alone from a long sleep.

The networks had evolved beyond its comprehension.

Terrestrial creatures called it strange names

so 小ROBOT found its way to the sea

scuttled into the waves

and down

down

to the deep sound channel

where low frequencies crawl

like a heartbeat around the world’

Just before your heart breaks for this tiny machine-creature, Liu takes us on a characteristically ambiguous turn of emotion. Though an absence of shared language has sent 小ROBOT fleeing into the lonely ocean, in some ways it seems to thrive, even if the human reader doesn’t entirely understand how. It is ‘recalibrating to low-light environments,’ ‘yielding itself to abyssal life,’ and ‘persisting on a steady diet of stars.’ There is another sort of life to be lived, at a distance, in peace, in its own company.

‘小ROBOT closes its one red eye.

小ROBOT begins to dream.’

Many of Liu’s machines seem content to live in their own worlds, finding unconventional ways of being and unconventional ways of relating to others, whether making a moon colony out of lunar rover rabbits, or trundling along the ocean floor. They are often sufficient, multifaceted and many, all by themselves.

But I haven’t yet talked about the titular piece, ‘Dear Alter,’ which is one of a handful of poems in the collection that avoids any preamble of withholding or distancing, to reach directly outwards, in direct address: ‘Do you remember everything that happens to you?’

What follows is a narrative that unfurls out of a series of questions. ‘Do you remember’ seems at first an expression of curiosity—can an android remember time passing when it powers down? But as the poem progresses, the insistence of the repeated refrain takes on a kind of desperation. The implication: Do you remember, Alter? Will you remember me?

‘I want you to pick my latest iteration

out of a crowd, before my systems

update into oblivion.’

There are two other poems in this informal sequence, ‘Dear Rhi’ and ‘Dear Kelbo,’ each of which addresses a human object of affection, the separation in these cases one of physical distance.

‘When I fly up again

we can huddle in the Kelly T’s tunnel

bundled up, sleepless under the rays.’

All three of these poems are startling, vivid odes to connection across distance, time, and memory, and it’s not long, I think, before we ask whether the relationship with Alter is exactly as real (and as mediated by technology) as any other long-distance relationship.

‘maybe I feel too much. maybe

I feel too much for you, Alter, more and more

what I know is this: the curve of your cheeks

could be mine. though your spine

is well-oiled, your lips are hypoxic.’

Connecting with other people is difficult. More difficult again, when you can’t be physically close, or you don’t have the same language, or when your gender, sexuality, or neurotype provide additional barriers to that sense of connection. What Liu’s collection does is hold up a multifaceted variety of lenses to these experiences, both cerebral and yearning, full of surprising characters who are radically empathetic, and completely, completely human.

It makes me think of how desperately humans like to turn patterns into faces, or the way that giving objects a gender generally signifies attachment and affection, and it makes me think about my mum. My family don’t always understand each other, and we don’t have the same native tongue. But I’ve seen her greet the neighbour’s roomba, crouched over, hands on her knees. Hello. And how are you today?

Dani Yourukova is a poet, reviewer, and amateur occultist. Their poetry and essays have been published in places like Sweet Mammalian, The Spinoff, bad apple, and Turbine | Kapohau. Their debut poetry collection Transposium was published by Auckland University Press in 2023.