Pastoral Care

Pastoral Care by John Prins. OUP (2025). RRP: $35. PB, 246pp. ISBN: 9781991348104. Reviewed by Erica Stretton.

John Prins’ debut short story collection Pastoral Care probes at the nature of care, of caring, and of safety: what can be sacrificed to stay safe? Prins is a master of pressing hard on small details to evoke emotion, and his varied characters are multi-layered, shaded knowingly in dark and light.

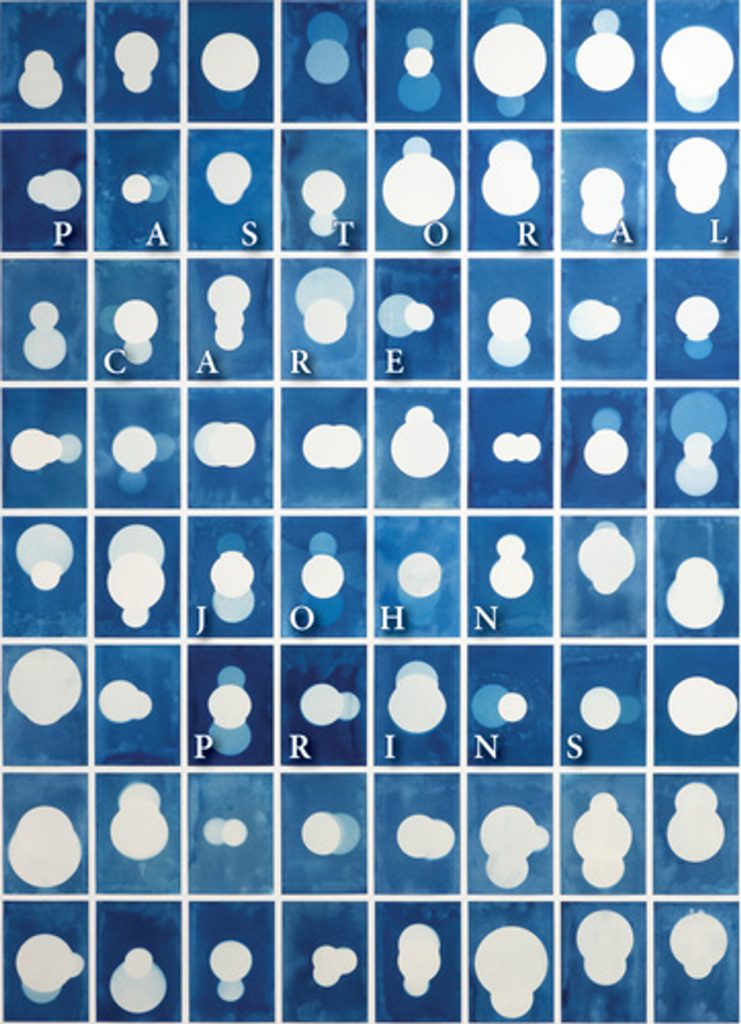

The book’s blue and white cover artwork, Blue Field by Gavin Hipkins, is striking and geometric, with an unstructured element within each field. Those white lights give it the sensation of busy-ness, and somewhat obscure the title, which seems appropriate given Prins’ emphasis on pertinent, poignant detail. Throughout the collection, the reader questions which detail will be key, which points to the heart of the story?

Many of the nine stories in this collection are outwardly about parenting or care. Caring responsibilities, care for oneself, care for another, care for the people who are buying a house. Should you care, do you care, how far must you care? In ‘Lake Pukaki,’ battered from her relationship with much older Ross, Flo has to save someone she’s only just met—‘she had to wake the guy up and keep him warm’—giving this stranger the ultimate in intimacy, her naked body. In ‘The Falls,’ Liam cares for a family bach that has a dark, personal colonising history. He does it properly: ‘only last summer, Liam repaired a leak in the roof and re-laid the entire floor,’ while resenting that if it were sold, he could care for his own nuclear family. But his brother insists on ‘recycled kauri, for which they paid too much.’

Masculinity is probed. Masculinity is turned inside out. But Prins doesn’t apologise for his characters; he observes with a wry and dispassionate eye. In ‘The Falls,’ when Liam’s daughter has a raging fever and emergency care is needed: ‘Gina was the one for a crisis. She’d know what to do. He needed that drink …’ In A Safe Passage, where Nicole sees her partner Steve through eyes that are both shaded and clear: ‘Nicole told Steve to leave his vigilante justice bullshit alone. –How can I protect you, he said, when you won’t listen to me?’ She has to grapple with safety, and whether the roof over her head is worth it, as Steve abuses those around her. Sometimes, she’s complicit, and other times, she holds onto her own self to stay intact: ‘Nicole doesn’t do sad anymore. There’s no time for idle emotions, no guilt, grief, or despair.’

Bernard in ‘But Baby, I Love You’ has his purity disturbed when his publisher suggests turning his poetry about his love of his son into a book on romantic love. ‘There was so much to be ashamed of,’ he says. In an interview with Gail, radio host, he sweats as she poses prescient questions, trapping him on his motivation in amongst an honest appraisal of the literary scene. He’s trapped, ‘the air too thick. If he had to hurt someone to escape, then that was what he’d do.’ But despite this, he soldiers on with the interview, knowing he has his child with him, the words coming to his tongue too opinionated, and better left unsaid on radio: ‘the literary scene is too small, too naive, too earnest, too unsophisticated, too obsessed with identity …’ Each word proves his own point, but later he explains it wasn’t all he needed to say: ‘all readers ever looked for was themselves. People were not being taught how to read.’

The final titular piece in the collection is a novella of 120+ pages. The probing and testing themes that echo across most of the collection burst fully to life here. Quoted at the top are lyrics from Louden Wainwright’s ‘The Swimming Song’: ‘This summer I might have drowned / But I held my breath and kicked my feet.’ Paul, a high school teacher with two small children, a marketing specialist wife, living in an affluent area in a house paid for by his in-laws, is at breaking point. All around him is responsibility, and compromise, and challenge, and ‘there was no respite. Not anymore. Not since Milly was born.’

Paul has a dilemma, whether to quit his job and ‘go corporate.’ This would be a betrayal of his own values—but he lives in Ponsonby, in a house that his in-laws helped purchase, which also sits uneasily against his skin. Throughout the story, he lets go of, sabotages, or pulls apart the confines of his life and his beliefs, forgetting to kick. In one section, he’s had a good lesson with his class and is high on his own competence inspiring teens, only to be turned inside-out by the class on the next page: ‘there was some kind of group chat dedicated entirely to humiliating him.’

But at the very end of this piece, Paul is rescued from the depths he’s wandered to and promoted. The reader, who was almost lost with him in an avalanche of pertinent details and side alleys, breathes a sigh of relief. Looking back over the whole collection, at Prins’ determination to probe the depths of what people can tolerate, misunderstand, and volley, testing the mind and strength of conviction, I wonder if this profusion of detail is a testament to our modern lives, and the whole point.

Erica Stretton is a writer, editor and reviewer from Tāmaki Makaurau. She has a Master of Creative Writing (First Class Honours) from the University of Auckland and was awarded a 2024 Surrey Hotel Residency. Her fiction has been published in Headland, Mayhem, Flash Frontier, ReadingRoom, and takahē.